Goodbye Old Number One

This column was written circa August 25, 2000 on the occasion of the death of the famous Duck Man, Carl Barks.

There’s a certain amount of sadness today in the city of Duckburg, Calisota.

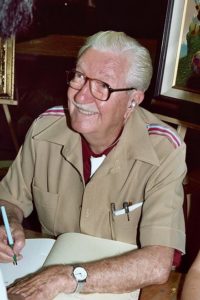

Carl Barks, who made Duckburg and its web-footed residents come to life has passed into comic book history at the age of 99. To the millions who grew up with his stories of Disney ducks on magical adventures — not knowing the name of the man who wrote and drew them until years later — he will live forever. Understand here, that when it comes to comic book creators, we are possibly talking about the greatest of them all.

Carl Barks had a special talent.

He could write and draw his stories on two levels. For kids, stories of Donald Duck and his three nephews, Huey, Dewey, and Louie, were high adventure. For adults, there was comedy and satire that the kids never realized was there. I enjoyed these stories as a child, then, read them again as an adult, finding them more pleasurable than ever.

Barks’ backstory is simple enough.

Carl Barks at the 1982 San Diego Comic Con. Photo by Alan Light. Licensed by Creative Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Carl_barks.jpg

He was born on March 27, 1901 and worked at a variety of jobs before settling down at the Disney Studios in 1935. His job was to think up gags for Disney cartoons such as Donald Duck. He remained a “story man” until 1942, when he became a freelance cartoonist.

He began his duck career in comics by drawing the April, 1943 issue of Walt Disney Comics & Stories — a ten-page Donald Duck story. With the next issue, he began the writing chores as well, and continued doing so for twenty-three years. He was not allowed to sign his work, and many people assumed Walt Disney was actually creating the comics.

But there was this “thing” about Barks’ work that the other writers and artists didn’t seems to have. Call it “atmosphere” or “style”. Whatever it was, it was so superior to other funny-animal strips (and most serous strips as well) that Barks’ Walt Disney’s Comics & Stories were soon selling about 3,000,000 per issue — perhaps thirty times what today’s comics sell.

And Barks did it all; he wrote the scripts, penciled and inked the art, and even did the lettering. When some other writer/artist teams would fill in, it was quite apparent to young readers. Barks became known as simply “the good artist.” It would be decades before he even knew that an entire fandom was springing up around his work.

What was it that made Barks great?

Most likely it was his awesome talent as an artist and as a storyteller, combined with the fact that he never “wrote down” to his audience. To Barks, the kids who thrilled to his stories were worthy of the best — or perhaps Barks was just incapable of giving less than his best. As the stories began to mount, the cast of characters in Duckburg grew and the stories became more textured.

Perhaps the best remembered Donald adventure was called “Lost in the Andes” where Donald and the boys traveled to Peru to solve the mystery of square eggs discovered in a museum. One of my favorites is “Land of the Totem Poles,” in which Donald takes a sales job only to find that his territory is the frozen north and his product to sell is a steam calliope.

In these travelogues, the ducks inhabited an obvious comic book world — but the backgrounds were impeccably researched and rendered by Barks. A story might take place in British Guiana in search of a valuable one-cent magenta stamp, to the deserts of Africa looking for oil, or to Alaska searching for gold — but the locales would always be correct.

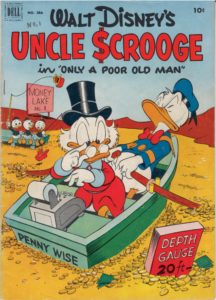

In a 1947 story called “Christmas on Bear Mountain,” Barks needed a wealthy relative for Donald, so he created the miserly Scrooge McDuck. Possibly intended as a throwaway character, Scrooge returned again and again because the possibilities with such a character were endless. Scrooge had a “money bin” filled with bills and coins that Scrooge would swim in — and toss the money into the air and let it fall on his head.

The Beagle Boys always wanted that money — just as the evil duck Magica De Spell wanted the first dime Scrooge ever made — Old Number One. Also known as the Number One Dime.

Old Number One. Scrooge kept it framed on the wall, or sitting on felt inside a glass display case. Growing up in a relatively poor family, I was enthralled by Scrooge’s wealth, and vastly impressed that he had managed to hold onto his first dime. (I might mention here that I still have my first dollar — a “Peace” silver dollar given to me by a grandfather on the occasion of my birth.)

I learned from Scrooge the importance of money — how hard it is to obtain, and to hold onto — and yet, the importance of obtaining it in an honorable manner. Scrooge always earned what he got, and in the end, he always had a heart of gold as well.

Four Color Comics #386 (1952) also known as Uncle Scrooge #1. From the collection of the author. Scanned by Lynn Woolley for WBDaily.

How did Scrooge get his money?

Not in computers like his modern day counterpart Bill Gates! No, Scrooge was a sourdough, scouring the frozen north for gold, and landing the “goose egg nugget” near Dawson in the Klondike.

In one 1952 story, he remembers a stash of nuggets and heads back to Dawson with Donald and the boys where he’s reunited with an old flame: Glittering Goldie who owes him a substantial amount of money. Scrooge, being Scrooge, demands it back. But Goldie, with wounded pride, admits that she lost everything she got from Scrooge — using it to take care of children who were orphaned by mining disasters. In the end, Scrooge goads her into a gold hunt, but rigs it so that Goldie will find the missing nuggets. Goldie’s pride is saved. But to save his own, Scrooge tries to hide the good deed from Donald.

Barks’ Christmas stories were always a highlight for his readers, and none is better than “Christmas in Duckburg.” In this marvelous story, Scrooge makes a bet with another rich duck that he can find a Christmas tree taller than the clock tower — 100 feet. Scrooge sends for the tree, but the other wealthy duck hires the Beagle Boys to steal part of the tree so that it won’t be tall enough — and so he won’t have to eat Scrooge’s spats.

Meanwhile Scrooge decides to do something really nice for the town this Christmas. While Donald is up north fetching the tree, he sends a telegram asking for 100 wild geese to eat the weeds of Duckburg. But the message gets mangled and Donald thinks it asks for “meese.” He returns to Duckburg with a too-short tree and two Moose which were all he could find. Scrooge is in danger of having to eat an old boot.

As it turns out, Scrooge has also come up with a Ferris wheel for Huey, Dewey, and Louie, and with the tree rising up on the wheel, it reaches the clock tower. The rival duck has to eat spats. No episode of “I Love Lucy” ever had more twists and turns.

Video: “Duck Tales” was inspired by the work of Carl Barks.

After hundreds of brilliant stories, Barks finally laid down his pen — and picked up a brush.

He began to paint scenes or cover re-creations from his duck stories. The paintings were exquisitely done, and sold for thousands of dollars to collectors. As the years have gone by, Barks paintings have come to be viewed as masterworks, selling for vast amounts of money. Wire stories say a 20-by-25-inch Barks oil sold in 1996 for $230,000, and another oil brought $500,000 in 1998. Amazing numbers for a gentleman artist who worked in obscurity for decades.

Now, the master is gone, but he will never be forgotten.

His stories of Donald and his nephews, and of his own creations — Uncle Scrooge, the Beagle Boys, Gladstone Gander, Gyro Gearloose, the Junior Woodchucks and so many more — will be reprinted for generations. His artistry will continue to be on display in the galleries of Disneyland and Walt Disney World. Fine art collectors will continue to pay big money for his oil paintings. His stories will remain as fresh as the day they were first published. That Old Number One Dime will forever be ensconced in its rightful place in Scrooge’s money bin.

But just for a while, turn down the lights on the old clock tower in Duckburg and lower the comic book flags to half staff. Carl Barks now belongs to the ages, and even crusty old Uncle Scrooge is shedding a tear.

Carl Barks: March 27, 1901 – August 25, 2000

Lynn Woolley is a Texas-based author, broadcaster, and songwriter. Follow his podcast at https://www.PlanetLogic.us. Check out his author’s page at https://www.Amazon.com/author/lynnwoolley. Order books direct from Lynn at https://PlanetLogicPress.Square.Site. Email Lynn at lwoolley9189@gmail.com.